'Lew the Jew' and tattoo origins

How a nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn helped create modern tattoo culture

Today, down the block from my apartment, a local tattoo shop was offering free tattoos. There was, not surprisingly, a long line of folks, mostly young people with only a few visible tattoos, waiting to get in.

That tattoo shop owes its promotional strategy, and perhaps its existence, to a man known as “Lew the Jew.”

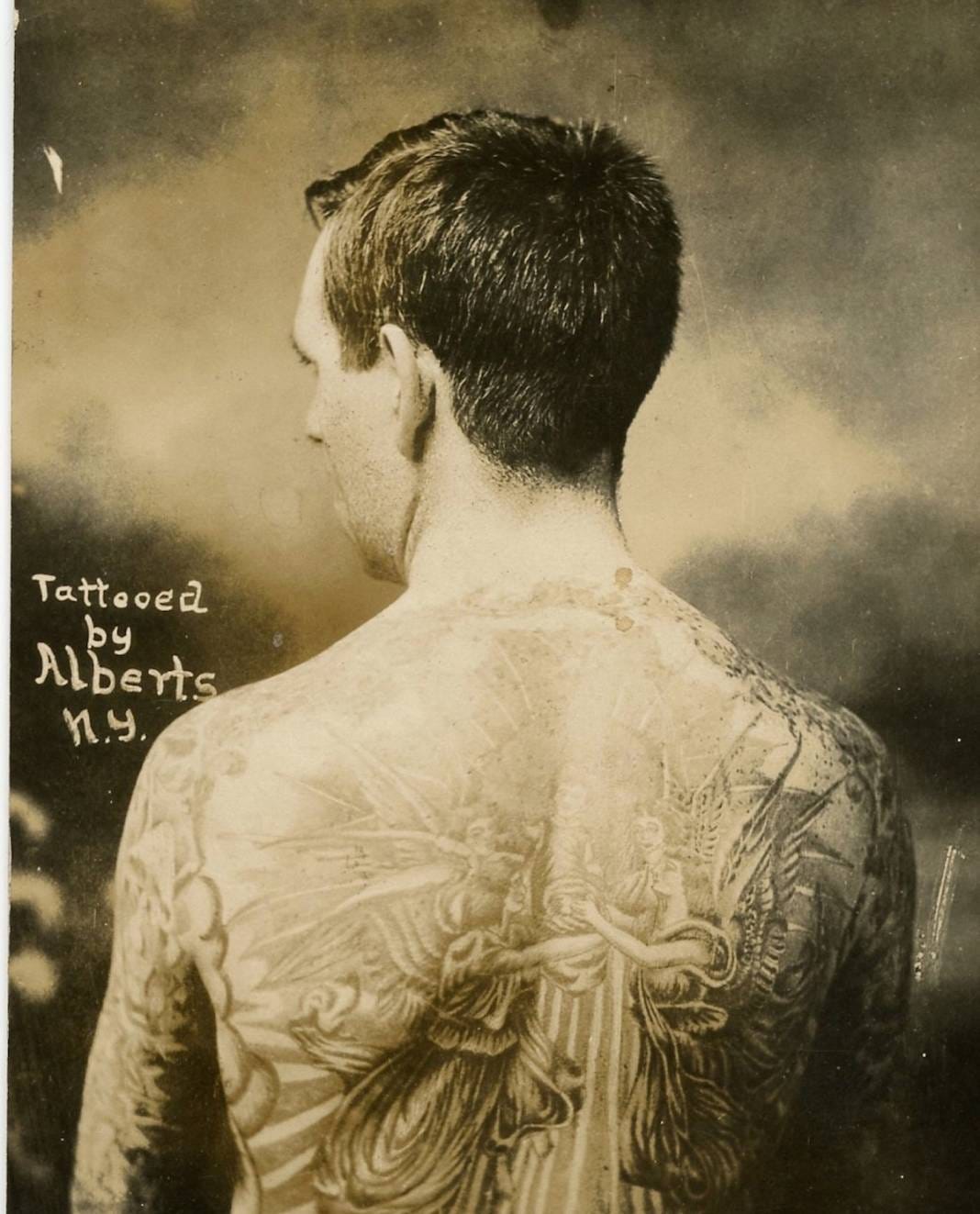

Walk into any modern tattoo shop and the first thing you’ll notice is books of tattoo designs. Those designs, and often designs hanging on the wall, are called “flash.”

Flash are drawings that the tattoo artist can do without any preparation. You don’t need a consultation, you don’t need a discussion. You can just point, and say, “That one.”

Albert Morton Kurzman, born in 1880, was the son of Jewish immigrants. He was a New Yorker by birth, and was a student at the Hebrew Technical Academy where apparently he learned drawing, metal and woodworking. His first job was designing wallpaper, which supposedly influenced his tattoo designs later in life.

Don Ed Hardy, perhaps the most famous tattoo artist in the world, wrote and published a book called “‘Lew the Jew’ Alberts: Early 20th Century Tattoo Drawings” from which much of this newsletter derives its content, but Hardy in turn credits a 1933 book by Albert C. Parry called “Tattoo: Secrets of a Strange Art.” Parry managed to interview Lew the Jew himself for the book.

Kurzman entered the Army in 1899 and fought in the Spanish-American War. He was first tattooed in the military and may have learned how to tattoo at that time as well. Leaving the Army, Kurzman began selling his tattoo designs to other tattoo artists.

Kurzman’s history as a wallpaper designer “eventually led to him developing new tattoo designs in the form of what we now call flash,” Hardy wrote. “His creations became the basis for iconic 20th century flash.”

Back in those days, there were no mechanical tattoo machines. All tattoos were hand-poked, as they had been for centuries, until Sam O’Reilly patented the first electric tattoo machine in 1891. Kurzman set up shop in O’Reilly’s old parlor in the Bowery section of lower Manhattan, and later was involved in a new design patented by Charlie Wagner.

Wagner became a success and started hiring tattoo artists, among them Kurzman who began calling himself “Lew the Jew Alberts.” Hardy noted that both Wagner, whose name was originally spelled Weigner, and another well known tattooist of the era, Joe Lieber, were also likely Jewish.

“At any rate, Kurzman chose a nom du needle that emphasized, rather than disguised, his heritage,” Hardy wrote.

That period of tattoo, beginning with the advent of electric tattoo machines, is widely considered the start of modern tattoo culture. There was something of a tattoo renaissance going on in the Bowery, and the manner in which tattoo shops operate now, as well as the style of what is now thought of as classic Americana tattoo, in large began in shops run by Wagner and Alberts, and others of their generation.

But the popularity of tattooing waned during Prohibition. Alberts nee Kurzman moved his shop to Newark, New Jersey, and according to Hardy, was the only tattoo artist listed in the city directory at the time.

Kurzman died in Brooklyn, on Oct. 8, 1954, aged 74.

Hey there. This newsletter, examining the intersection between seemingly opposing cultures — tattoos and Jews — is sent out weekly and for free, at least for now. I don’t use social media too much anymore, so I am hoping to get some organic growth. If you found this interesting or amusing, would you mind sharing it with someone else? I’d be forever grateful. Thanks a mil — Jordan