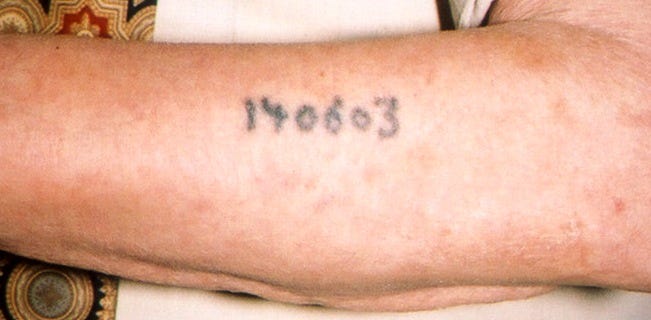

There are few images of the Holocaust more identifiable than simple tattooed numbers on a withered arm.

Tattoos were used by the Nazis in only one concentration camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau, but their use has remained emblematic, nearly a century later, of dehumanization and genocide.

Only prisoners who were deemed able to work were assigned numbers. Those who were considered too weak or old to work were sent directly to the gas chambers. Initially, serial numbers were assigned to prisoners in the infirmary and were sewn on prison uniforms, but as the population in the camp grew, the use of sewn-in serial numbers was deemed inefficient and tattooing became commonplace, beginning with Soviet prisoners of war and then, in the Spring of 1942, all incoming Jewish prisoners.

“A guy who got a number was lucky,” the Sydney Jewish Museum quoted Lou Sokolov, a tattooist at Auschwitz. “Why? Because he didn’t go straight away to the crematoria.”

The numbers used were part of a series, the first for male prisoners, beginning in 1940 and running through January 1945 reaching the number 202,499. Female prisoners began to arrive in 1942, which began a new series. In all, 90,000 female prisoners were assigned numbers. When a large number of Hungarian Jews began arriving at Auschwitz in 1944, numbers began with the letter “A” and ran through 20,000, at which point the serial numbers began with “B” and started from the beginning. There were 15,000 men with tattoos beginning with “B.” Women’s serial numbers began with “A” and ran through 30,000.

The method of tattooing employed by the Nazis at Auschwitz was perhaps unique. As Gabriel Wolff explained in 2023, the method was a variation on the traditional hand-poke tattoo method, though instead of a single needle a series of needles were used to pierce the skin, like a stamp, in the shape of the numerical sequence and then ink was inserted through the needles.

Several tattoo stamps used by the Nazis were discovered in 2014. Elżbieta Cajzer, Head of the Museum Collections at the Auschwitz Museum, described them then as “a-few-millimetre-long needles, which were inserted into a special stamp to create a specific number.” The finding, however, was incomplete, consisting of “one zero digit, two threes and two stamps which may be sixes or nines,” Cajzer said.

It’s worth quoting Italian Jewish chemist Primo Levi, who wrote in his book “The Drowned and the Saved” as follows about a tattooed prisoner:

“He is Null Achtzehn. He is not called anything except that, Zero Eighteen, the last three figures of his entry number; as if everyone was aware that only a man is worthy of a name, and that Null Achtzehn is no longer a man. I think that even he has forgotten his name, certainly he acts as if this was so. When he speaks, when he looks around, he gives the impression of being empty inside.”