Why is this tattoo different than all other tattoos?

Jews don't usually get tattoos, but why bother writing about it?

Perhaps it’s time for a recap. Some new subscribers have signed on (I am profoundly grateful for each and every one), and they might need a bit of a primer to catch up before the test next week.

The question I get most often when I tell people that I’m writing about the Jewish tattoo taboo, is “why that, of all things?”

It’s pretty niche, to say the least. Jews make up a small subsection of the overall population, and Jews with tattoos are a tiny audience when compared to subjects like politics or celebrities or banana bread.

Ask a Jewish person about tattoos, and the first thing they’ll tell you is wrong: You can’t get buried in a Jewish cemetery. It’s simply not true.

It’s possible that some Jewish cemetery boards of directors refused to bury people with tattoos, but even that is unlikely. Would they refuse to bury a baal teshuvah (someone who has returned to the faith)? Would they refuse to bury an Auschwitz survivor?

The prohibition against tattoos derives from one mention in the Torah, included in a section about burial rites (which is probably where the “you can’t get buried with a tattoo” myth emerged from).

There are, of course, many Jewish laws -- 613 of them, to be precise, not counting all the many cultural prohibitions that aren’t explicitly against Jewish law, or are questionably so. Jews don’t eat seafood, or combine cheese with chicken, or eat animals with cloven hooves, or cremate the dead or speak in between the prayer over the wine and the prayer over the bread on Shabbat.

So, why write specifically about tattoos?

To put it simply, there are moments throughout Jewish history when the tattoo taboo has been broken and every time, it says something about both cultures. Here’s a quick rundown of a few of those moments:

Some academics believe that the prohibition against tattoos was not always as absolute as is currently thought

Ancient Jewish mystics “inscribed” the word of God on their bodies as part of magical rites.

The Beta Israel, the Ethiopian Jews who were brought to Israel in the 1980s and 1990s, arrived with tattoos on their faces.

Modern tattoo culture, including how tattoo shops currently run, was largely defined by Jews in the Lower East Side of New York in the early 1900s.

The Nazis tattooed Jews against their will at Auschwitz, and the grandchildren of those survivors have more recently gotten tattoos that replicate those numbers.

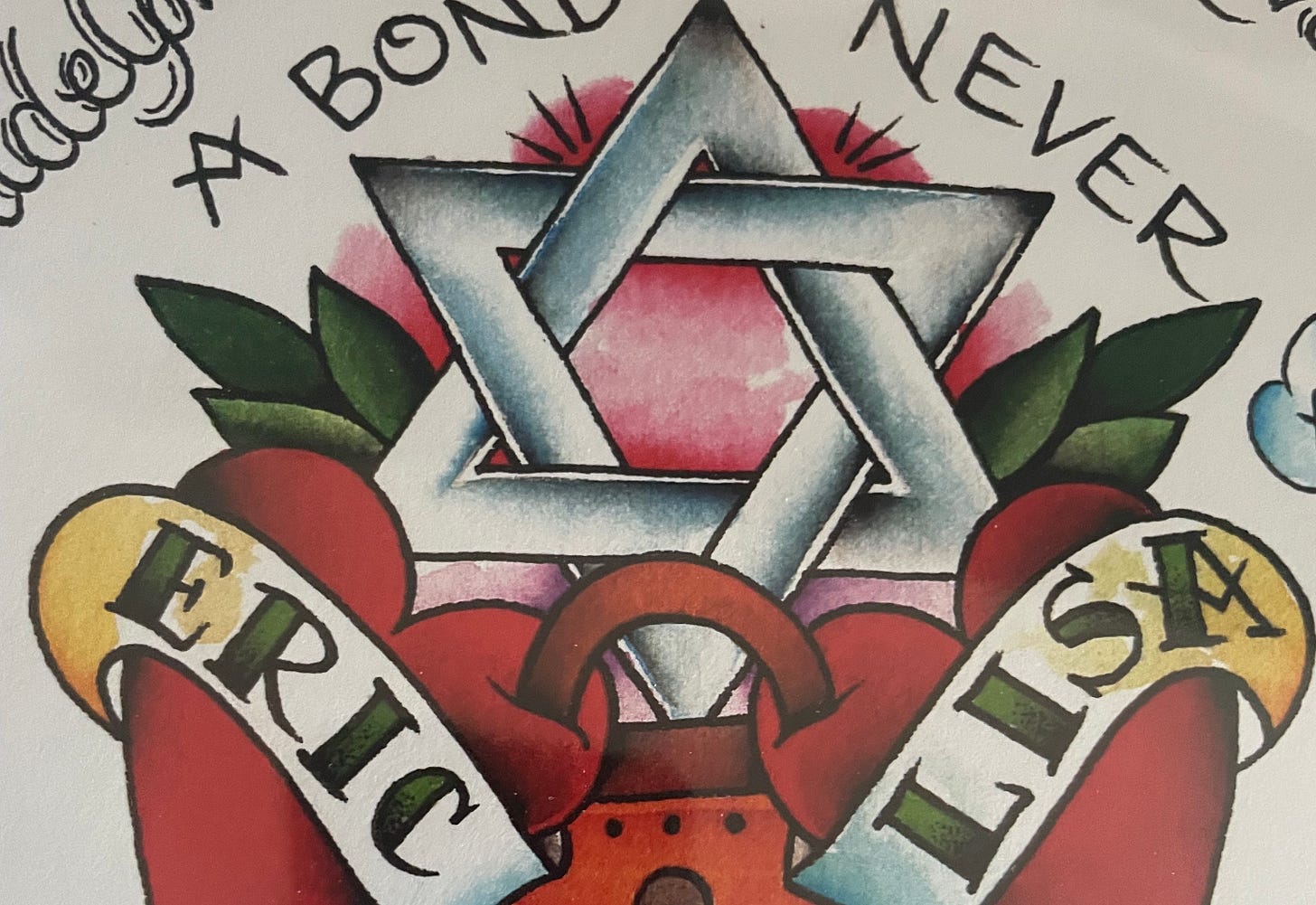

Many young, less religious but culturally Jewish people have Jewish iconography tattooed on their bodies as a means of identification.

After Oct. 7, many young Jews got tattoos in memory of the people who died or were taken hostage in the attack.

There is a long history of tattoos in Russian prisons, and Jews of Russian descent in Israel have kept up the practice in Israeli prisons.

I also add the story of the Golem, the Jewish Frankenstein’s monster, who was brought to life by a word carved on its clay body, though it’s more metaphorical than historical.

So, in this newsletter (and the book I am compiling from it) we will meet Jewish tattoo artists, academics, rabbis, and just Jewish people who, for their own reasons, have been tattooed.

See you next week!